With the Open just a few short days away, I wanted to look at how the design of a CrossFit workout can affect the results we see in competition. I considered writing a last-minute manifesto on why HQ should

not program 7 minutes of burpees for the first workout, but I've resigned myself the inevitability of that happening on Wednesday night, so let's just move on. (Reverse jinx right there? Maybe...)

It goes without saying that CrossFit is a sport that demands its athletes be strong in all areas of fitness. Any glaring weakness will eventually be exposed, and no one is winning the CrossFit Games (or even making it there) with a major deficiency in any area. That being said, simply because a movement comes up in a workout does not tell us exactly what type of emphasis is placed on it. In my earlier post "What to Expect From the 2013 Games and Beyond," I summarized all the movements used in the last two years of competition based on how much of the total score they represented. To do this, I assumed that in a workout with 3 movements, they were each worth 1/3 of the score. While this does give us a good idea of the value of each movement in aggregate, the truth is that it doesn't tell the whole story.

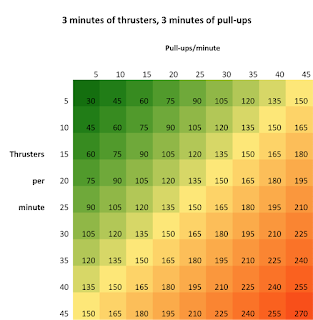

Consider two workouts, both comprised of thrusters and pull-ups. Workout A is 3 minutes of thrusters followed by 3 minutes of pull-ups, with the total number of reps as the score. Workout B is "Fran" (21-15-9 rounds of thrusters and pull-ups). Below are two charts showing how an athlete would fare given his/her rate of pull-ups per minute and his/her rate of thrusters per minute. The red cells represent better scores and the green cells represent poorer scores.

Look first at the top chart. You can see that the scores are identical along each diagonal, moving from top right to lower left. That's because you can exactly offset a deficiency in one movement with an equivalent improvement in the other one. Doing 30 pull-ups per minute and 20 thrusters per minute produces the same score as 25 per minute of each.

Now look at the chart for Fran. In this case, the best scores always occur when the athlete is balanced. Performing 25 thrusters per minute and 25 pull-ups per minute produces a time of 3.6 minutes (~3:36). Improving the pull-ups to 30 per minute but decreasing the thrusters to 20 per minute produces a time of 3.8 (~3:48). The reason for the discrepancy involves some pretty simple algebra.

In a workout where a certain number of reps has to be performed at each station, the time needed to finish a station is (reps needed) / (reps per minute). If we improve our speed by 20%, that lowers the time for that station to (1 / 1.2) = .83 times the original time. If we decrease our speed by 20%, it increases the time for that station by (1 / 0.8) = 1.25 times the original time. In total, our new time is ((.83 + 1.25) / 2) = 1.04 times the original time. So you can see the punishment for a poor movement is greater than the reward for a strong movement. In a workout where there is a fixed time domain per station, we don't have this effect.

One way to quantify this effect is to look at the drop in performance in a workout that occurs when we drop the speed of one movement by 20% and increase the other movement(s) by a total of 20%. So if there are three movements, we drop one by 20% and increase the other two by 10%.

I'll also need to make some assumptions are necessary about the "base" speed for each movement. "Fran" was an easy example above because it's reasonable to assume that on average, thrusters and pull-ups take a similar amount of time for most athletes. That isn't necessarily the case with other workouts. My estimates for these base speeds for each movement are roughly based on my own results, but I also was trying to represent a relationship between the movements that is pretty typical for CrossFitters. But I will admit, there are no exact answers for this. Changing these assumptions based on the level of athlete will certainly change our answers, and I'll go more into that in a moment.

Let's look at a few workouts from the Open in years past. A few notes first:

- The result for each movement is what I'm calling "leverage." It represents the decrease in performance if we drop the speed of a given movement 20% and increase the others by 20% (in total).

- I'm using a using a 20% decrease for each movement, but that's just an arbitrary choice. Any other choice (10%, 30%, 40%, etc.) would yield slightly different results, but the concept is the same.

- The term "Rate" here means the speed, in terms of stations per minute (it's just the inverse of the minutes per station, which I listed first because it's easier to comprehend).

- I calculated the score as the number of stations, not the total number of reps. That's because all reps are not equal: one double-unders doesn't mean as much as one muscle-ups. All stations aren't necessarily equal, either, but it's better than simply counting reps.

OK, onto the results.

WOD 12.3 is pretty much a classic CrossFit workout. For most athletes, all three movements take a similar amount of time, although I think it's fair to say the push jerks were generally the slowest, especially as the workout wore on. You see that each movement is leveraged a decent amount, but athletes who struggled on push jerks were punished the most.

For WOD 11.1, based on the assumptions I've used, the snatch was the more critical movement, despite being the second of two movements. For athletes who have solid double-unders, they will almost certainly be slower on the snatches. This means that a deficiency on the snatch is really exposed, whereas the double-unders weren't punished too much, so long as the athlete didn't have a catastrophic weakness.

WOD 12.4 was an interesting case. The wall balls took up a big chunk of time for all athletes, while the double-unders should be comparatively quick for athletes who are pretty competent with them. For most athletes, the muscle-ups are going to be slow, especially at that point of the workout. But what is also key here is that the order of movements is critical. Athletes who struggle with wall balls will be punished hard, and they may not even make it to the double-unders or muscle-ups, hence we see the 7.5% leveraging factor. Conversely, the double-unders and muscle-ups were actually negatively leveraged, meaning this athlete would actually benefit if he/she got 20% slower at that movement but 10% faster at each of the other two. I'm sure that shorter athletes who may excel at muscle-ups but struggle with wall balls can probably relate to this fact.

Now let's look at 12.4 once more, but for an elite athlete who is gunning for about 1 full round.

You can see that for the elite athlete, the muscle-ups become much more important, while the wall balls aren't quite as critical as for the intermediate athlete. Still, though, slightly slower double-unders were not a problem if you could offset that deficiency with strengths elsewhere.

Now, I tend to prefer workouts like 12.3, where the stations have relatively similar time domains and no single movement can make or break the workout. However, I believe there are reasons for designing workouts where certain movements are leveraged significantly more than others. For one, since the Open is designed to be inclusive, the workouts will almost always start with the movement that is easier to complete for one rep. This allows the maximum number of athletes to compete. I'd be stunned if we ever see a workout in the Open start with muscle-ups.

Another issue is that certain movements are prone to have a wider range of speeds than others. For instance, wall balls are basically capped around 30-35 reps/minute due to gravity, so it takes more reps for athletes to really separate themselves. With something like muscle-ups, however, a set of 20 muscle-ups can separate even the best athletes in the world by quite a bit. So perhaps it makes more sense to design the workout so that the wall ball stations take twice as long as the muscle-up station. I notice this a lot with rowing: if you're not careful, the row can become a throwaway movement (as far as competition is concerned) unless you devote a considerable portion of the workout to that movement. The difference between a strong and weak rower just isn't that wide, even over something like 1,000 meters that takes more than 3 minutes.

So what can we take away from this? Well, personally, I learned a few things in doing this analysis, or at least put some numbers behind some things I (and likely others) sensed intuitively:

1) You can't offset any weakness by simply being stronger in another area. In general, it pays to shore up weaknesses across the board rather than improving in areas you are already strong.

2) This concept varies depending on the workout. In some cases, you can actually benefit from being particularly great in one area and weaker in others. Sometimes this means the workout isn't perfectly designed. However, it could be because HQ is programming the workout to account for the fact that certain movements take more time/reps to separate athletes than others.

3) Order matters in an AMRAP. We saw this clearly in WOD 12.4. And although I didn't show it as an example above, the thuster/pull-up ladder (WOD 11.6 & 12.5) also is a great example. For athletes with a base speed of 15 reps/minute on each movement (105 reps for the workout), the thrusters are leveraged at 5.7% and the pull-ups are leveraged at just 1.4%.

4) Testing movements together, with a required number of reps on each movement, will punish weaknesses more than testing them separately. For instance, something like AMRAP 10 of 10 snatches (95/65), 10 burpees will punish the specialist more so than AMRAP 7 of burpees followed by AMRAP 10 of snatches. (Sorry, I know I promised not to argue against the 7 minutes of burpees, but I couldn't resist...)

So these are some intriguing conclusions, but what can we do with this moving forward? Well, there are two ways I can see this type of analysis being applied moving forward:

1) Once a workout is released, athletes can start to understand what the keys to the workout will be. If we plug in some assumptions for a certain level of athlete, we can see how much each movement is leveraged based on the workout design. That might provide some insight on how to attack a workout. For 12.4, we can see that the hitting the gas on the wall balls might be worthwhile, even if the double-unders suffer a bit. Again, this may have been intuitive to many athletes/coaches, but seeing some numbers can help to clarify things.

2) We can assess what worked and didn't work in programming a competition. In theory, you could actually look back and calculate how long it took (on average) for athletes to complete each movement, and then use that information to get a clear picture of how much each movement truly was leveraged. Did you adequately test the movements you wanted to? Was the workout balanced? If not, was that by design? Just because a workout seemed friggin' awesome when you wrote it up doesn't mean it actually turned out to be a great test of fitness.

Anyway, that's all for today. Time permitting, I'm hoping to post something each week during the Open. No guarantees on exactly what those posts will look like or what type of analysis I'll be doing, other than to say I'll be talking about the Open. So pop on over this way from time-to-time during the week - it's got to be a healthier habit than leaderboarding.